Prison camps have generally received less attention, overlooking the fact that they were products of

those horrific battles. Most works relating to this southern Maryland prison camp rarely reach the

depth of research and discussion of both prisoners and guards, which is presented to understand

better what both prisoners and guards experienced. Previously published works generally depict the

guards as cruel and inhuman, displaying little compassion for their charges. Such alleged treatment

by the guard force was not always the case at Point Lookout.

Post-war works reflect biased opinions based solely on the writings of prison survivors. Contemporary

writers on the subject have accepted these memoirs, stories, and reflections as the final word without

questioning their validity. The results presented challenge other researchers who have accepted what

was written in the post-war years as the final word.

Point Lookout Confederate Prisoner of War Camp

As

the

number

of

prisoners

steadily

increased

after

the

battle

of

Gettysburg,

it

became

evident

that

the

number

of

current

Union

prisons

was

not

enough

to

hold

them

all.

As

no

major

prisons

had

been

opened

or

facilities

converted

since

the

Confederate

defeats

at

Fort

Henry

and

Fort

Donaldson

in

1862,Quartermaster

General

of

the

U.S.

Army,

Montgomery

Meigs,

ordered

Brigadier

General

Daniel

H.

Rucker,

Chief

Quartermaster,

to

establish

a

prison

camp

at

Point

Lookout,

Maryland,

capable

of

incarcerating

5,000

prisoners

with

area

enough

to

add

an

additional

5,000

prisoners, or more, when needed.

Point

Lookout

was

established

on

August

1,

1863,

and

became

the

largest

prisoner

of

war

camp

during

the

war.

It

was

located

at

the

extreme

tip

of

St.

Mary’s

County

on

the

long,

low

barren

peninsula

where

the

Potomac

River

joins

the

Chesapeake

Bay.

It

had

been

a

resort

area

with

hotels,

boarding

houses,

cottages,

and

commercial

establishments

prior

to the Civil War.

The

site

was

leased

to

the

federal

government

in

June

1862,

and

quickly

became

a

significant

government

installation.

Even

though

the

site

was

comparatively

isolated,

it

could

be

easily

protected.

At

the

extreme

end

of

the

peninsula,

near

the

lighthouse,

a

1,400-bed

hospital

was

constructed

comprising

sixteen

buildings

arranged

in

a

circle.

Hammond

Hospital

was

supported

by

a

large

wharf

to

receive

supplies

and

the

wounded

soldiers

that

arrived

from

battlefields.

The

hospital

complex

included

a

number

of

storehouses

and

stables;

laundry

and

dining

facilities;

and

additional

quarters

for

officers,

doctors,

surgeons,

and

Union

troops.

The

hospital

became

one

of

the

largest

and

busiest

medical facilities in the Union's service.

A

fifty-acre

site

located

about

a

half

mile

northeast

of

the

hospital

was

selected

for

the

new

prison.

Work

soon

began

by

enclosing

the

area

with

a

twelve-foot-high

fence,

with

a

catwalk

constructed

along

the

top

of

the

fence

for

the

guards.

The

prison

was

divided

into

two

sections;

one

area

of

approximately

thirty-eight

acres

for

the

enlisted

men

and

the

adjoining

site

designated

for

officers

of

approximately

seven

to

eight

acres.

The

inside

of

the

prison

was

a

barren,

flat

stretch

comprised

of

a

mixture

of

part

sand

and

part

clay.

All

of

the

prisoners

were

to

be

sheltered

in

tents

instead

of

barracks.

The

camp

was

prone

to

coastal

flooding

as

the

peninsula

is

approximately

two

feet

above

sea level.

The

prison's

official

name

was

Camp

Hoffman

but

was

seldom

referred

to

by

this

name.

Before

long,

the

prison

became

the

most

populated

and

largest

prison, at one time holding over 20,000 prisoners.

The

first

guard

detail

assigned

to

the

camp

was

the

2

nd

and

12th

New

Hampshire

Infantry

Regiments.

Other

guard

units

assigned

included

the

4

th

Rhode

Island

Volunteer

Infantry,

the

10th,

11

th

and

20

th

U.S.

Veteran

Reserve

Corps

Regiments,

and

the

139

th

Ohio

Infantry.

On

February

25,1864,

the

36th

U.S.

Colored

Infantry

Regiment,

followed

by

the

4th

United

States

Colored

Troops

and

the

5th

Massachusetts

Colored

Cavalry,

would

act

as

prison

guards.

These

regiments

would

soon

be

followed

by

other

U.S.C.T.

units.

United

States

Navy

warships

and

gunboats,

such

as

the

U.S.S.

Minnesota and the ironclad U.S.S. Roanoke, would patrol the waters on both sides of the peninsula.

The

first

commandant

was

Brig.

Gen.

Gilman

Marston.

He

was

replaced

in

December

1863

by

Brig.

Gen.

Edward

W.

Hinks,

in

April

1864

by

Col.

Alonzo

G.

Draper,

and

in

July

by

Brig.

Gen.

James

Barnes.

The

first

prisoners

arrived

in

late

July

and

by

the

end

of

the

year,

the

population

was

more

than

9,000

prisoners. By mid-summer 1864, it was over 15,500 prisoners.

The

prisoner's

tents

were

set

up

in

ten

parallel

streets

referred

to

as

“divisions”

that

ran

east

to

west

within

the

prison.

By

late

1864,

the

divisional

streets

would

increase

to

thirteen

to

accommodate

the

surplus population in the prison.

LIFE & CONDITIONS:

All

prisoners

lived

in

the

overcrowded

tents

and

shacks,

with

no

barracks

to

protect

them

from

heat

and

coastal

storms.

There

were

several

different

kinds

of

tents

that

the

prisoners

used.

Each

row

of

tents

were

labeled

as

a

division

and

would

hold

1,000

or

more

prisoners.

The

majority

of

the

different

types

were:

A-tents

(5

men),

Sibley

tents

(13-14

men),

Hospital

tents

(15-18

men),

Wall

tents

(3-8

men),

Hospital

fly’s

(10-13

men),

Wall-tent

fly’s

(3-8

men),

and

Shelter tents (3 men).

The

eastern

wall

of

the

prison

whose

border

ran

along

shoreline

of

the

bay,

was

provided

with

gates

that

were

opened

to

permit

prisoners

to

bathe,

wash

clothes,

fish

and

gather

oysters.

The

many

water

sources

available

for

drinking

were

usually

contaminated.

The

wells

that

supplied

the

water

for

the

camp

were

usually

dug

too

shallow

and

contaminated

easily.

It

would

not

be

until

the

last

months

of

the

war

that

the

federal

government

arranged

delivery

of

fresh

water by boat to both Hammond Hospital and the prison.

There

was

never

enough

food

or

firewood;

both

were

strictly

rationed.

Rats

were

a

major

source

of

protein

for

some

inmates,

and

catching

them

became

a

favorite

sport

in

the

camp.

Rations

were

supposed

to

consist

of

pork

two

out

of

three

days,

with

beef

on

the

third

day.

The

rations

were

served

twice

a

day,

between

the

hours

of

8:00

and

9:00

a.m.

for

breakfast

and

1:00

to

2:00

p.m.

for

dinner.

The

bread

wagons

would deliver fresh bread generally after the midday ration.

There

were

weekly

inspections

of

the

prisoners

and

prison

camp,

in

which

the

prisoners

would

have

their

shelters

inspected

for

contraband

(illegal

possessions).

Flooding

of

the

prison

compound

was

frequent, often flooding their shelters and making living conditions practically unbearable.

Because of the topography, drainage was poor, and the area was subject to extreme heat in the

summer and cold in the winter. This exacerbated the problems created by inadequate food, sanitation,

clothing, fuel, housing, and medical care. As a result, over 4,000 prisoners died during the twenty-

three months the prison operated.

Besides

chronic

diarrhea,

dysentery

and

typhoid

fever

had

become

epidemic

at

the

camp

while

smallpox,

scurvy,

and

the

itch

had

become quite common.

The

latrines

at

the

camp

were

built

out

over

the

bay

on

the

east

side

of

the

camp

for

use

in

the

daytime.

Large

boxes

and

or

tubs

were used at nighttime.

Daily

activities

in

the

camp

consisted

of

reveille

between

dawn

and

sunrise

and

followed

by

roll

call.

After

breakfast,

the

prisoners

passed

time

by

busying

themselves

with

a

wide

variety

of

occupations and pastimes.

There

were

still

22,000

prisoners

being

held

by

the

end

of

the

war

in

April

1865.They

were

eventually

released

in

a

combination

of

alphabetical

order.

By

June

30th,

all

prisoners

held

at

Point

Lookout

had

been released with the exception of those that were still bed ridden in the hospitals.

It

is

estimated

that

a

total

of

52,264

prisoners,

both

military

and

civilian,

were

held

prisoner

there.

Although

it

was

designed

for

10,000

prisoners,

during

most

of

its

existence

it

held

12,600

to

20,000

inmates. Only 50 escapes were successful at the camp.

More Details About

Point Lookout, Maryland: The Largest Civil War Prison

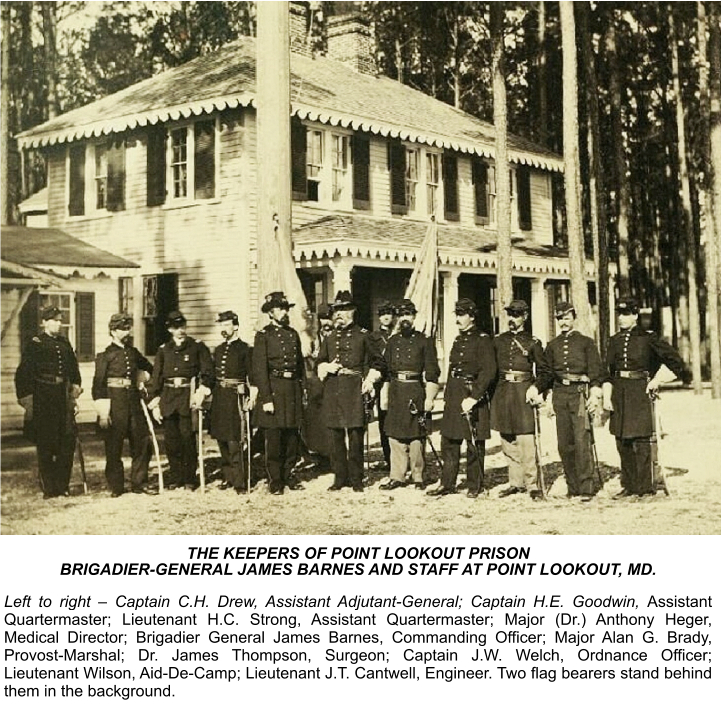

Prisoner and artist John Omenhausser of Co. A, 59th Virginia

Infantry documented his experiences while at Point Lookout Prison.

He drew 65 watercolors and put them in a sketch book. Several

libraries have this sketchbook including the New York Historical

Society: You can view the sketchbook here:

https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A31569#page/17/mode/2up

Prisoner and artist John Omenhausser draws a scene on the

beach where prisoners gather crabs and one prisoner shows

another who has never seen a crab to smell his bug.

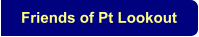

Dr.

Anthony

Heger

served

as

Medical

Director

of

the

hospital

at

Point

Lookout,

Maryland.

- Crickenberger Collection

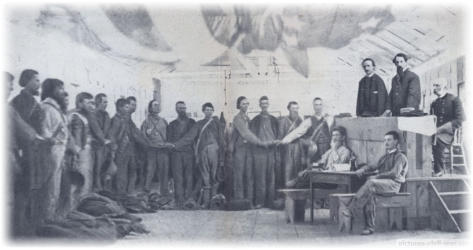

A

group

of

prisoners

stand

in

a

building,

with

the

U.S.

Flag

draped

across

the

ceiling,

each

with

his

hand

on

a

Bible.

A

Union

officer

stands

at

a

dais

administering the oath of allegiance to the Union

.

Copyright © 2025 Robert E Crickenberger

Point Lookout, Maryland:

The Largest Civil War Prison

By Robert E. Crickenberger

A Groundbreaking Book That Rewrites the Legacy

of the Union’s Most Infamous POW Camp

July 1863 – August 1865